Interdisciplinary Aspects of Longitudinal Pulses that Reversibly Cross a Phase Transition

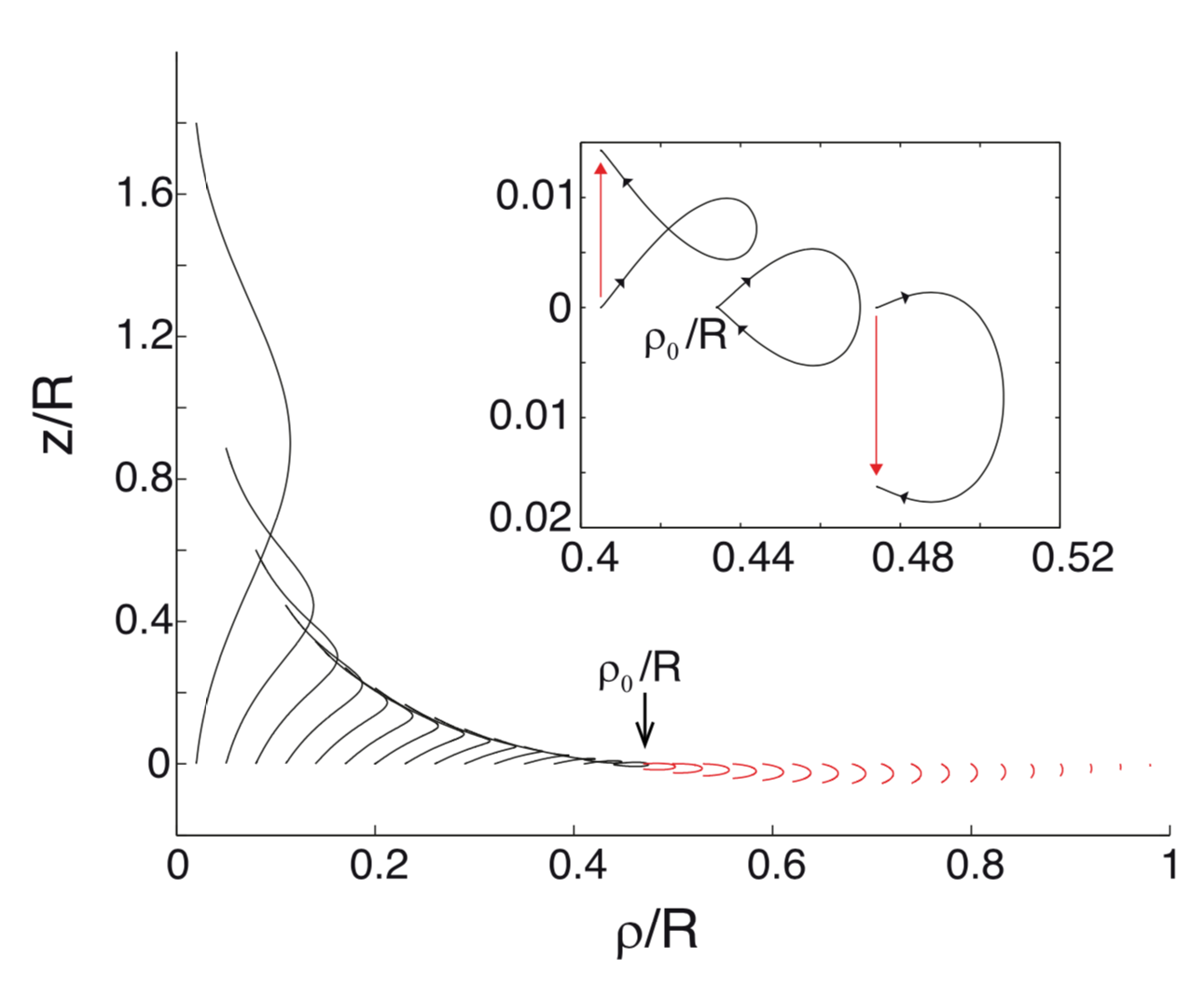

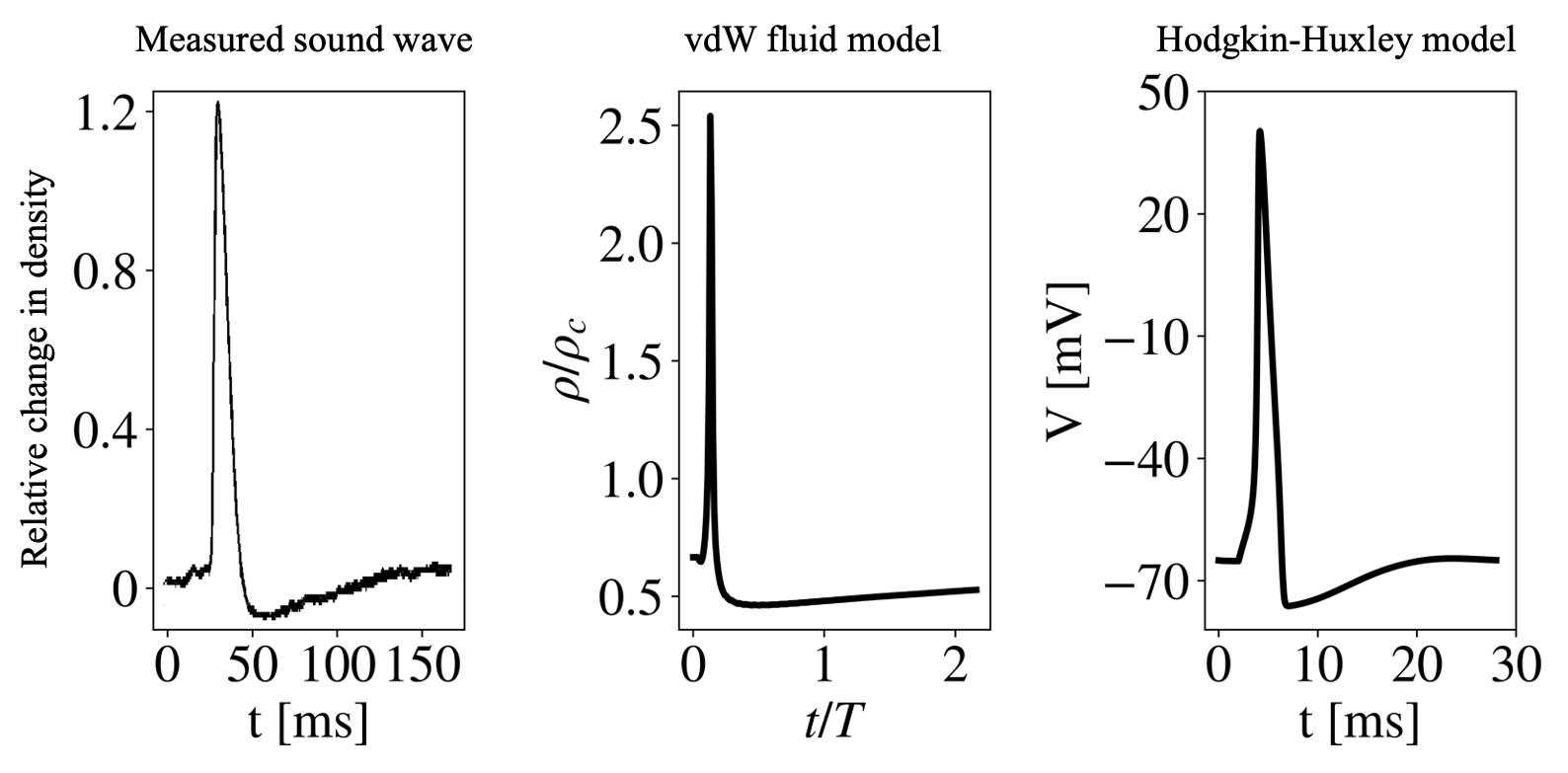

Biological Aspects: Longitudinal pulses propagating close to the lipid melting transition display unusual nonlinear properties strikingly similar to those of action potentials observed in excitable cells. The possible role of acoustics as a functional mechanism in living cells is intriguing, and this research area has hardly been explored. We use analytical and numerical tools to investigate these pulses, focusing on the interconnections between the mechanical, electrical, and chemical aspects of the lipid membrane, embedded proteins, ions, and solvent [10, 17].Physical Aspects: Novel nonlinear properties of sound, such as wave-wave interactions, emerge close to the phase transition. These lead to nonintuitive properties, such as the failure of the superposition principle resulting in pulse annihilation [9], as well as transient permeability changes that create oscillatory and excitability regimes [19].

Computational Aspects: Inspired by biological and artificial neural algorithms, the nonlinear properties of longitudinal pulses near the phase transition could be leveraged to create innovative material-based computing schemes aimed at decreasing energy consumption, enabling parallel operations, and expanding our computational toolkit in unconventional ways [23]. Investigating how information about the stimulus is stored within these pulses, we find that the system casts information about the stimulus into a high-dimensional space [10]. Furthermore, the pulse propagates in parallel both digital and analog information about the stimulus amplitude, and a collision between two pulses acts as a fading memory [20].

Ion-induced volume transition in polyelectrolyte gels and its role in biology

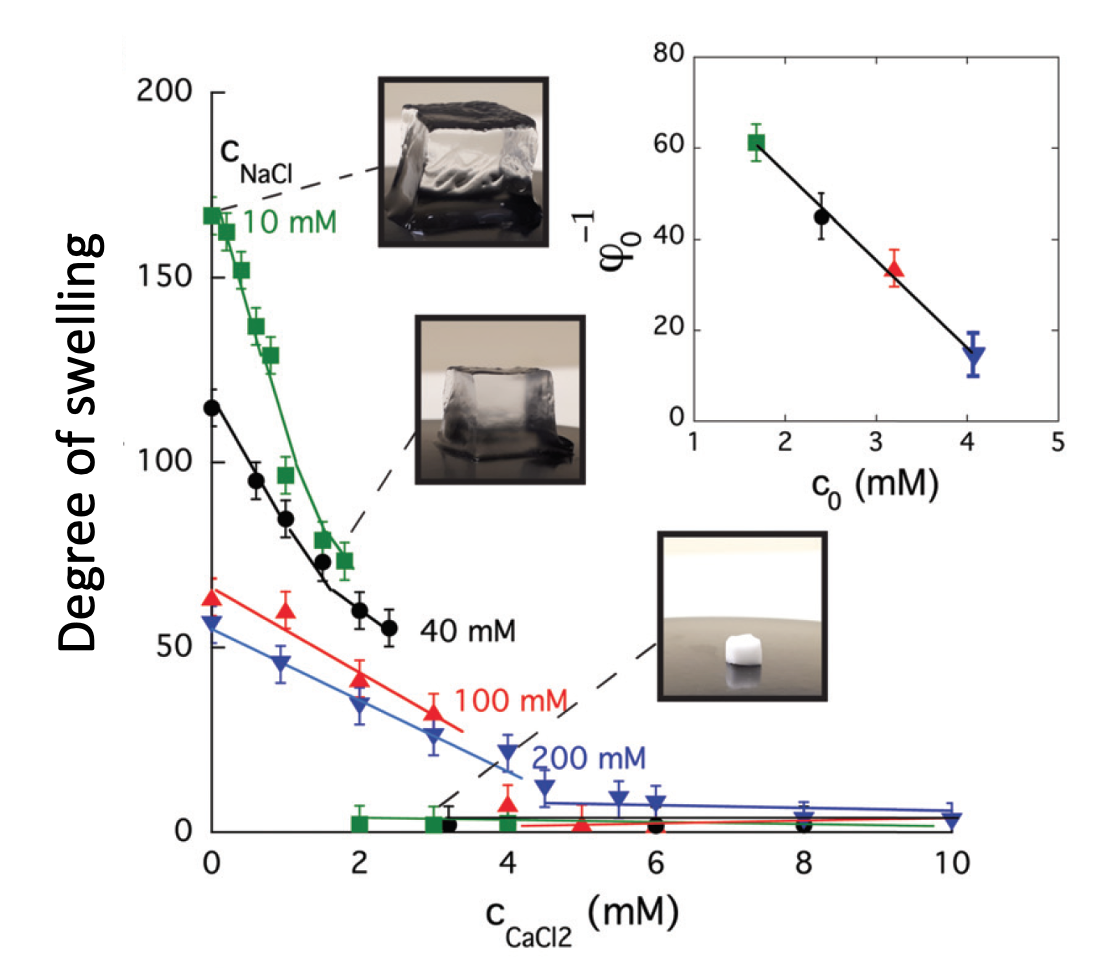

Polyelectrolyte hydrogels are soft complex systems made of charged crosslinked macromolecules, solvent, and counter and co-ions. Many types of polyelectrolyte hydrogels demonstrate an abrupt volume transition in response to minute changes of external environmental stimuli, such as temperature, ionic composition, solvent quality, pH, and electric field [11, 13]. Similar phenomena are found abundantly in living systems [15], and are also widely used in various man made applications. In this project we attempt to shed light on several distinct biological processes such as: compaction of DNA molecules, release of secretory products, and changes in the hydraulic flow in the xylem of vascular plants, by developing a dynamic physicochemical framework that accounts for the interaction of charged polymers, solvent, and ions [18].

Surface deformation during cellular excitability

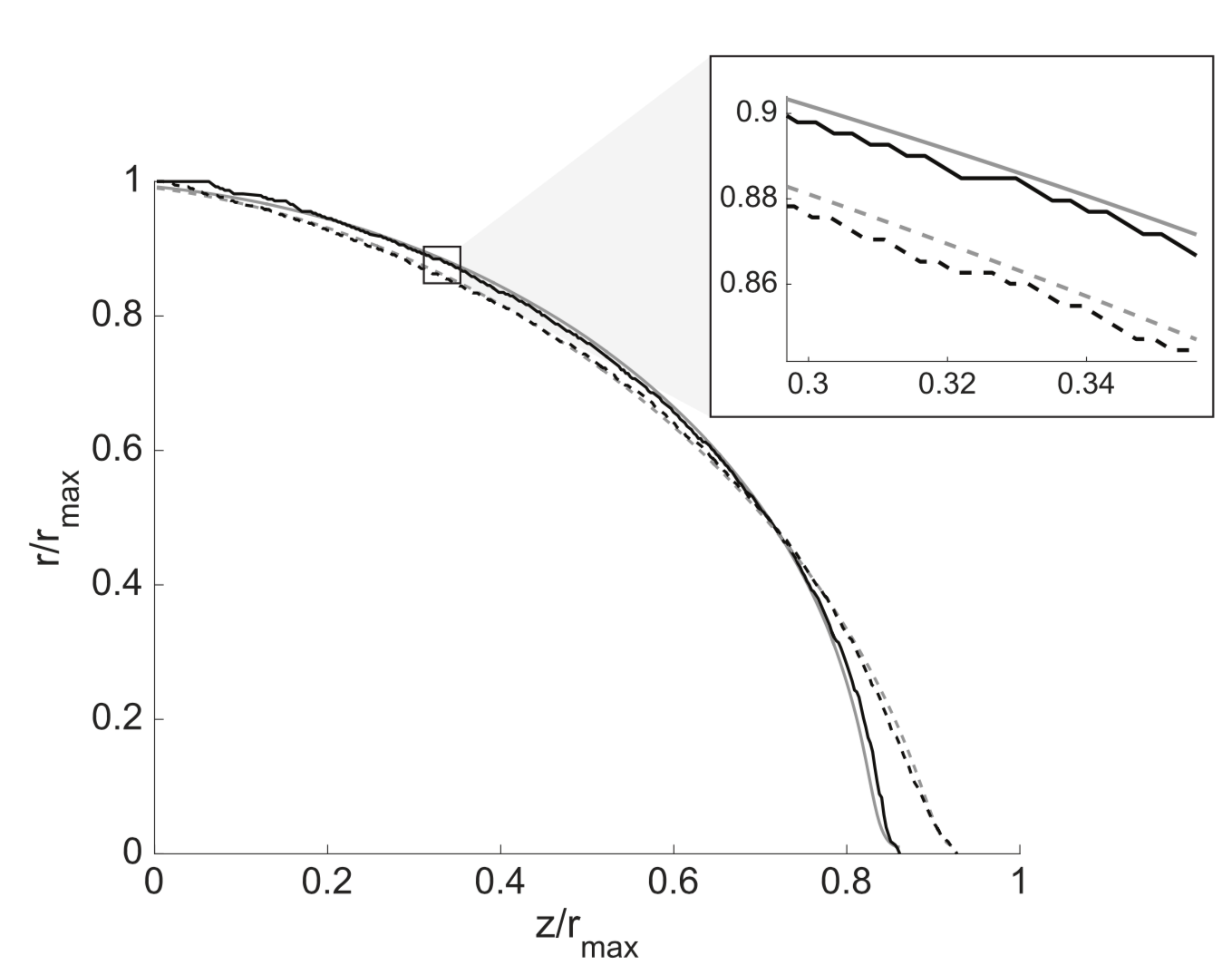

The excitation of many cells and tissues is associated with observable mechanical changes. In neurons, mechanical deformation of the cell surface is usually revealed as a swelling followed by a contraction, with amplitudes of ∼1–10 nm. We previously demonstrated that in large excitable plant cells the rigid external layer (cell wall) hinders the underlying deformation, and observed significant cellular deformation that co-propagates with the electrical signal with amplitudes of ∼1—100 m. These transient cellular deformations are captured by an elastic model of the cell surface, suggesting that elastic properties of the surface are crucial for the explication of the phenomena [6,7]. Starting from very simple mechanical models, we introduce empirically motivated terms to better understand the mechanoelectrical coupling, its effect on intracellular components, and the nonelectrical information propagating to neighboring cells. The resulting models are of relevance for the description of several biological processes in their native state as well as for the understanding of certain clinically significant pathologies (primarily neurological ones).

Active transport induces drag of intracellular fluid

Active transport within the cell cytoplasm includes steady trafficking of different organelles and vesicles actively transported by motor proteins using chemical energy. We previously showed that indirect hydrodynamic interaction (flow-induced drag) that exists between actively transported cargoes and soluble particles is sufficient to account for the most relevant experimental observations pertaining to the slow-component transport in axons, which plays an important role in cell development and maintenance [3]. Further work in this area will aim to connect fundamental hydrodynamic principles with emerging properties of cell development. For instance, the rate of axonal growth might be shown to depend on delicate features of the microtubules facilitating the transport and the organelle transport rate.